January 14: Hammock in a Deprivation Tank

Games are machines for feeling. You open the box, set the board up, power up the console, hit start, and let your self pour through it. It may be that books, films, and music are machines for feeling too, but if they are, we only understand them as such because games have literalized the process of semiotic reassignment and amplification that connect self to text. Here are some rules: pressing shift means this, pressing X means that, make this number go up so you can save the world again. Interlace those with stories, spaces, and characters you might recognize from elsewhere to supercharge them with pathos and comedy and baby you've got a stew going. I love games because of the way I feel as my body and brain begin to understand what each one is doing. I love the feeling of having my own expectations for how things work being rewritten as new tactics, new powers, and new branching stories open up. I am not in it for the power fantasy, but I am in it for how the power fantasy might hold my buzzing brain for a few moments like a hammock in a sensory deprivation tank.

I want to share a few of my favorite games with you from 2025. These games each did something for me that I didn't see coming. They each connected with something deep in me. For some that means they brought me back to my best friend's living room, 11 years old, taking turns killing a million dudes onscreen with a pair of lunatic tonfas. For others that means they offered the thrill of an aesthetic whole - that amazing feeling when impossibly distant ideas or feelings suddenly click together like a key in a lock.

It was, by any metric, a bad year for the video game industry. More studio closures, more private equity, more layoffs, more entanglements with genocidal regimes and union-busting thugs, more, more, more, more.

The quality of the games this industry produces - or I should say, the people of this industry produces - never justifies or offsets the oppressive machinery of these awful organizations. Games might be machines for feeling, but these companies are often just machines of the orphan-crushing variety. Games being good and games industry being bad are obviously related ideas, but they aren't on either side of the see-saw, if you get my meaning. One thing being pushed far enough up doesn't push the other one down. I don't want to say that because the games are good, things will be all right.

But what I will say is that because the games are good, I am all right. Or at least, I can be for a while.

Dynasty Warriors: Origins

Few gaming subgenres have the raw appeal to me that musou games do. Musou games are a subset of action games focused on delivering one experience: fight through as many dudes on screen at once as the current year's technology is able to allow.Koei Tecmo's Dynasty Warrior series has been the standard bearer for this little genre since Dynasty Warrors 2, released for the PS2 all the way back in 2000. Since then, over countless mainline releases, spin-offs, and copy cats, the formula has more or less stayed the same for the venerable series: give the player some kooky weapons and let them loose in a stylized dynastic Chinese setting based on the 14th century novel, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, where they can let it rip on thousands upon thousands of unsuspecting footsoldiers. Sure the action, narrative, and aesthetics can get repetitive,

Dynasty Warriors: Origins represents the first real reboot for the series, adding in lots of modern design sensibilities that include a slick new overworld to traverse, a self-insert created character, and some reasonably compelling conversations with a whole cast of NPCs. As a result, it loses some of the high camp appeal of earlier entires in the title, but in return a blockbuster sheen that, for me at least, really enhances the game's central appeal: making you a hilariously overpowered god on the battlefield.

What surprised me was how much better Origins is than any of its predecessors at opening up the political and emotional stakes of Romance of the Three Kingdoms. I'm not saying it's The Last of Us or anything, but the game's main narrative conceit is offering players the choice on which of the three kingdoms they are going to support, and its a conceit that brought me closer to the dramatic energy of Romance of the Three Kingdoms than I'd ever been in a quarter century of playing these games. Added a nice little frisson to the experience that has me excited to dive back in when the DLC comes out. Maybe I'll even read the book.

Sektori

Asteroids is kind of a sacred text for me. I had a shareware version of it for my family's first DOS computer that I played endlessly. Something about the way the three lines of my ship moved through space, the way it moved with what felt like real physical weight and momentum, felt like the height of realism to me. Every near miss felt earned, every bullet on-target felt important. A good high score made you feel like Neo in the Matrix.

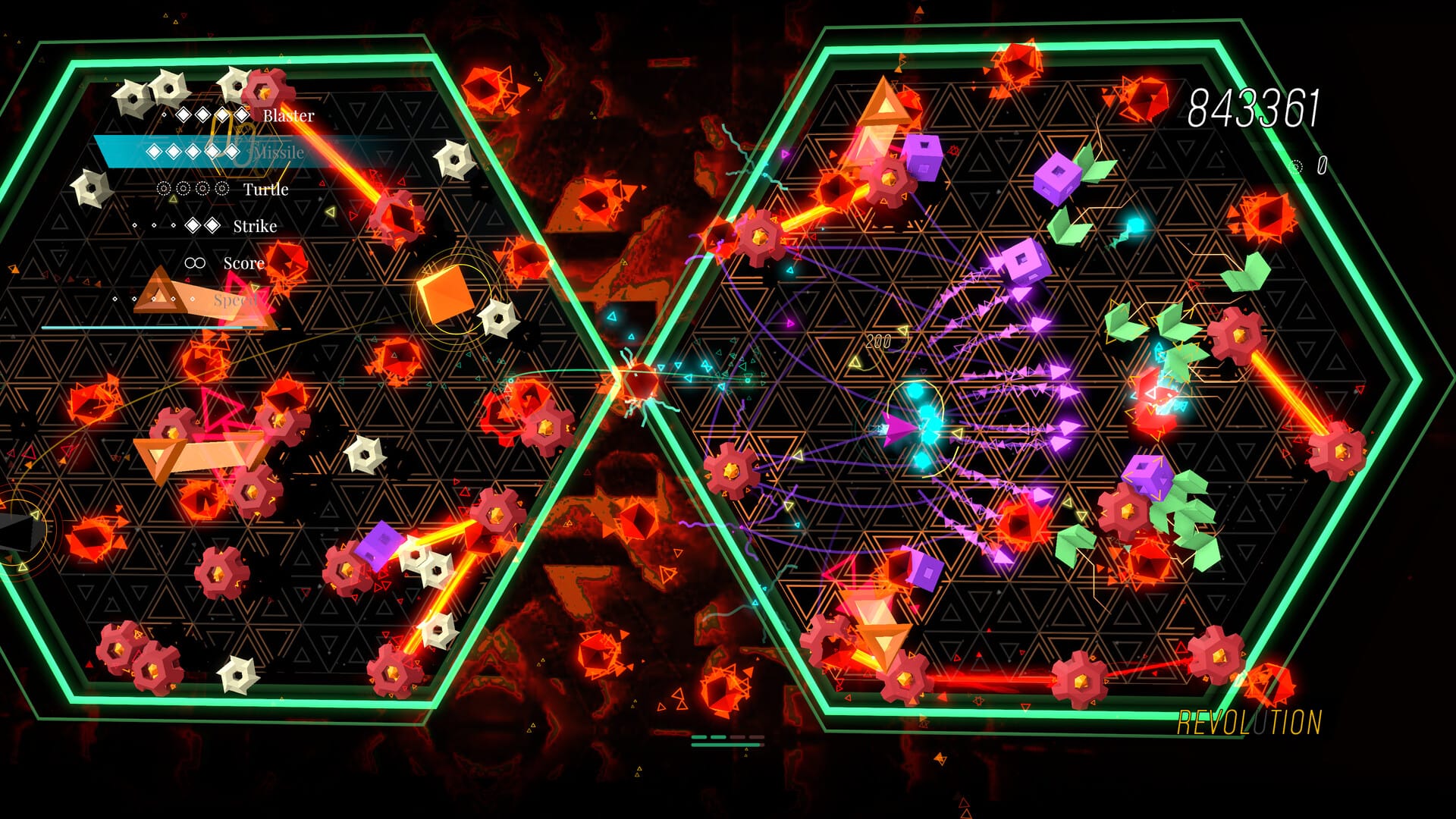

Sektori brought me back to that exhilaration and hasn't let me go since.

Sektori is the new twin-stick shooter by solo dev Kimmo Lahtinen, aka gimblll. In it, you pilot a ship from a top-down perspective through wave after wave of hostile, laser-light polygons. Like Asteroids or Geometry Wars, another classic in Sektori's lineage, Sektori is a game about pushing your piloting skills to the brink, cornering you with swarms of enemies, demanding you squeeze into ever smaller spaces, requiring you to think ahead of your reflexes and plan out your paths through the flashing lights. Sektori ups the ante by constantly changing the environment around you while asking you to make split second decisions about how to periodically improve your ship's capabilities. It's a frantic, frenetic, and often totally overwhelming to the senses, but I also found it to be strangely meditative. It's the kind of game that demands so much of your brain that it kind of just holds it for a while, letting you sink somewhere much more peaceful.

Ghost of Yotei

First-party Sony titles come with an intense and specific set of expectations. They are the video game world's de facto prestige titles, trading on the publisher's reputation for pushing the boundaries of high-fidelity graphics while offering serious-minded narratives, cinematically presented. I've played and liked most of these titles, though they often leave me with the sense that Sony is vaguely embarrassed to be making video games. Often these games tug at the sleeve, nagging like an anxious child trying to drag you to the toy section, see? We're just as good as movies!

Ghost of Yotei certainly shines with some of the same insecure sheen of Sony's deep, deep pockets; it's a big, bold AAA sequel with a huge open map and a steady stream of gorgeously realized mo-cap cutscenes. It even layers aesthetic gimmicks on top of the normal AAA rigamarole. Kurosawa mode, returning from Ghost of Tsushima, shades everything in black and white, layering a mono filter over the audio. And the new Watanabe mode which replaces the game's ambient sound with lo-fi hip hop beats to slay ronin to.

The big surprise of Yotei is that despite all the production values, despite the familiar revenge-story beats, despite the occasionally gimmicky aesthetic decisions, it understands the intimacy that video games offer players. It's a game about closing the distance between you, the player, and Atsu, the game's vengeful onryō. The menus seem designed to kick you back out into the world along with Atsu, wandering the beautiful ecologies of Edo-era Ezo. Battle reduces the abstraction of video game combat, its system of strikes and parries dangerous enough to make each hit count, narrowing your focus to the point of Atsu's katana. And whenever possible, Ghost of Yotei takes you out of the third-person action perspective that often underwrites player embodiment in these kinds of games, replacing it with first- or even second-person meditations on the heft of a new blade, the sizzle of a roasting mushroom, the satisfying clink of coins in a round of Zeni Hajiki.

To be clear, the main reason to play Ghost of Yotei is probably because it's a really well-crafted, engaging adventure, starring incredible performances (Jeannie Bolet as the mysterious Oyuki is a particular standout) and better writing than most games of its ilk. But for me, it's the way this game invests in drawing you closer to the sensations of being Atsu that sets it apart. It easily finds a place on my personal Mt Rushmore of open-world games.

Clair Obscur: Expedition 33

What can be said about Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 that hasn't already been said a million times? This inaugural title from French developer Sandfall Interactive translates the tried and true building blocks of turn-based Japanese RPGs into an aesthetic and narrative environment indebted to La Belle Epoque art and philosophy. The result is one of the more stunning experiences I've had holding a controller in years - maybe in my entire life. Rarely have I felt more trusted with the material by a game, and I mean that both in terms of the surprisingly dense systems underwriting the game's combat systems, and in terms of the thematic material Clair Obscur plumbs at every turn.

Clair Obscur is a game about the tension between hope and desperation. It's about finding a way to do the work even though there might be more virtue in accepting the work's futility. It's also about sisterhood and the beautiful, complicated moments which forge it. It's also about disability, and the walls erected by art and family meant to pen the experience of disability in. It's also about generational trauma and the role art plays in both healing and maintaining the hurt. Clair Obscur is a work of enormous imagination and heart, thoughtful where it would be very easy to be trite, and again, I mean that both in terms of its mechanical design and its storytelling.

I am constantly annoyed at the way people talk about games as though the playing of them and the meaning of them are separate things. I understand the temptation - most of our meaning-making habits revolve around charaters and narration, not attack combos and menu selection - but these mechanical things are meaningful too. Clair Obscur understands this, insists on it. An example: toward the game's end you'll receive an item that rewrites the limits of what your party can do in its battles. Things that once seemed impossible blossom into new tactical avenues, and it's thanks to the narrative discovery that rewrites, in an equally transformative way, everything you thought you understood about the characters you've spent so long getting to know. Clair Obscur understands that to play a game is to feel a game and it's a sad thing to waste all that feeling on stories that don't lalnd the hits on time.

Clair Obscur is unquestionably my game of the year. It's beautiful, brave, and thoughtful at a scale that constantly surprises.

Thanks for reading, as always. I'll be back next week to talk about four favorite books from last year. Or at least books that I read last year, even if they didn't actually come out in 2025. See you then.

Jordan Cassidy

Member discussion