February 5: A moment of reflection, always within reach

I told you the newsletter is back, and it is, but maybe not in exactly the same form as it's been. I started this thing in the mindset of a shut-in. A remote-working, white collar professional moored on an island of content in a sea of disease. Each newsletter I wrote was a message in a bottle thrown as far as I could muster, maybe my greatest act of faith in years. Four recommendations that each week I'd let run a little wild, see what they produced. And each week I'd peer into the analytics and see that around 70% would at least take a peek - it was the connective tissue to the crumbling world around me that I needed.

The material for the newsletter was born of a sudden, rushing intake of stuff - more TV, more movies, more music, more books. All filling up the spaces where I used to go to restaurants and hang out with friends. So the newsletter became a roving spotlight illuminating the things I liked as they cruised pass my line of sight. Putting together a few extra words to frame those recommendations each week was an added bonus.

But now, a confession. I'm just not watching, listening, playing, or seeing that much stuff these days. I've got a one-year-old now. I'm going to a chiropractor. I'm making videos. I'm pitching pieces. I'm looking for work. I'm playing games because that's where I'm trying to focus my writing. It's a tough state of affairs for a newsletter premised on making recommendations.

All of this to say, I'm expecting the format of this newsletter to fluctuate a bit through the next few months as I find a new point of equilibrium for it. I'll still bring the recs, but they might be deep dives with just one thing, or more free form essays. The goal will always be to put good stuff in front of you that you might have otherwise missed, you can count on that. Appreciate your patience for sticking with me as I figure the next stage of The Crossover Appeal out.

The Quiet Year

Tokens of Contempt and Connection

Our culture is saturated in post-apocalypse. The wasteland occupies a position of peculiar privilege in the American imagination, slotting right alongside high fantasy and star-faring sci-fi as genre setting du jour. If you're writing a book, making a game, or pitching a show, the post-apoocalypse has some built in crowd-pleasing scripts you can usually make use of.

Myself, I have never much liked thinking about the apocalypse. Not to say I haven't enjoyed my share of apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic media - I like Mad Max as much as the next guy - but there's a certain rugged individualism about straight-faced post-apocalypse that rubs me the wrong way. Post-apocalypse is the fantasy of survival, sure, but it's also the fantasy of collapse. To picture yourself as the lone survivor you must first imagine society as an obstacle to your self-actualization.

And look, we've all been on the wrong end of social mores at one time or another. Who hasn't passed an afternoon imagining the world's collapse and the great satisfaction we'll feel knowing that we made it to the other side and not all those people and expectations who've wronged us. But it's odd, right, that we've all dedicated enough time and resources as a culture to create a full cottage industry in service of that feeling. It's odd that when we think about what's on the other side of the apocalypse, we tend to imagine the unwashed scavenger and the brutal tyrant rather than the compassionate mother or the dedicated researcher.

Last week I played a game that helped me understand where else post-apocalyptic stories can go besides these violent fantasies of raw power. It's a small cooperative storytelling game called The Quiet Year, and even if you're not the kind of person who usually takes time out of their week to play make believe with other grown-ups, I think it's still worth your time. Especially if, like me, you've been watching the tear gas and jack boots flooding the streets outside and wondered about what an after to all this can look like.

The Quiet Year imagines a small community trying to rebuild after something awful happens. The awful thing that happened isn't important to the game beyond the fact that it creates a before and an after. You and your friends do not play characters within this community, but rather, abstract social and environmental forces. You determine, in other words, week-by-week, the story of this community, not as its heroes, but as a sort of narrative matrix from which its fate emerges.

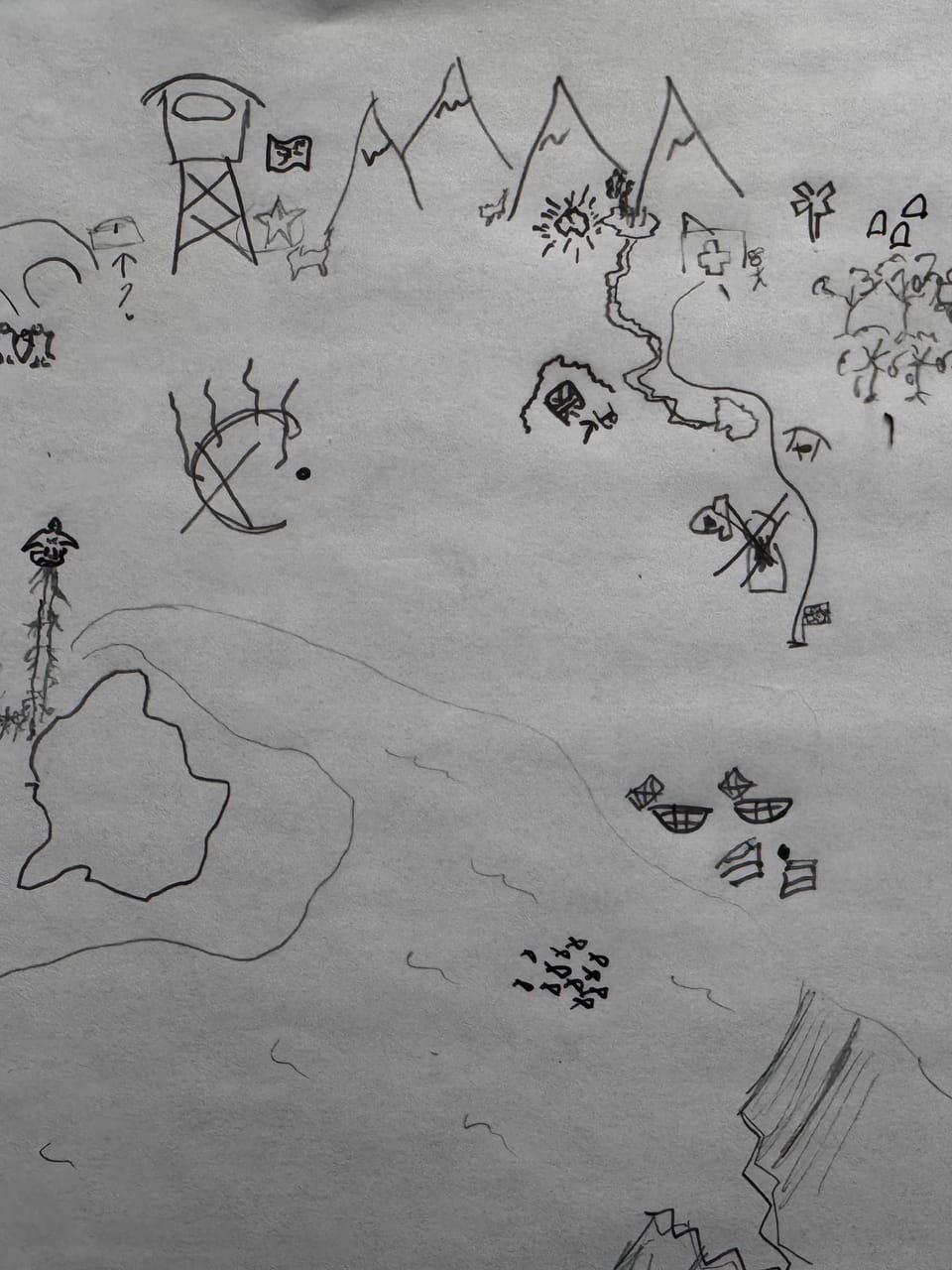

It's a game of conversations. You have a sheet of paper between you all that you take turns at the start filling in with some small details - a mountain here, a dilapidated mine there, a natural omen somewhere else still - and as the game unfolds, you continue adding to that map. On your turn you draw a card which tells you about a new challenge facing the community - you and you alone can resolve it. Then you do one of three things: start a project, discover something new, or hold a discussion. When you start a project, you point out something on the map that the community will now work towards. Maybe it's reopening the mine, or maybe it's going fishing in a mountain river. Whatever it is, it's some way for the community to work towards security, abundance, and maybe a future. When you discover something new, you draw a new feature on the map you've all made together. Maybe it adds a new resource for the community to leverage. Maybe it creates a schism between different factions your group has already been outlining. Either way, it's certainly something you'll need to navigate in the future.

The surprising heart of The Quiet Year however lies with your third option: holding a discussion. For lack of a better word, the other two options feel pleasantly gamey. Though open-ended, they both feel like moves. Holding a discussion is not a move. It's not even clear whether it takes place in the space of the community you're narrating or in the space of the narration between the players.

When you choose to hold a discussion, you'll propose a topic in the form of either a question or a statement. You might say, for instance, "We should not have banished the outsider. He had valuable knowledge that would have helped us come winter." Then, everyone at the table takes a turn responding. They must do so in just a sentence or two, and when everyone has had their say -- that's it. Your turn is over and the next player goes.

I've been thinking about the confusion I felt in that moment since we played. Games don't do this kind of thing. Storiesdon't do this kind of thing. They don't pause in the middle of the action to secure everybody's input and then offer no direct action in return. In a corporate setting if someone did this you'd call it a waste of time. There's nothing actionable here. It's not a move. But... I liked it. I really liked it. In fact, these discussions, held a half a dozen times or so in the course of our game, felt like the distinguishing feature of the experience.

The strangest thing about these discussions is how I couldn't quite figure out whether or not I was having the discussion as a representative of some faction within the world we'd built together, or if we were having it at the meta-layer, as storytellers commenting on one another's narrative choices. It's a productive fuzziness though, as it allowed us to tease out both the on-the-ground reactions to our choices we thought our little society might have while soft launching new ideas and directions the story could go. There's no opportunity for a back and forth in these conversations - no follow-up questions, no arguments. Instead, if you don't like what someone said, for whatever reason, you take a Contempt Token and keep it in front of you. These tokens accumulate slowly over the course of the game, stacking up as a physical reminder not only of the rifts emerging in the recovering post-apocalypse, but the tensions among the group as narrators too.

Tabletop games are chock full of tokens like these. Usually they're meant for exchange, whether for resources or points. Vouchers, in other words. But these are not like that. These are tokens in the sense that they mark a moment or a feeling, for no reason other than you felt it was worth remembering. They do not represent a score, the health of the community, or the best storyteller. Instead they index your personal relationship to the storytelling beats that you've forged togther with your friends. Token, as in a sign of connection, not token as in a coin, a currency.

These Contempt Tokens are the signal flares that help you navigate that fuzziness I mentioned earlier. I once took a Contempt Token when someone else held a discussion around the question: "Who in our community deserves to eat?" It was a question born of sudden scarcity - an awful but fair question. But in hearing it I immediately felt disgusted, imagining myself as a community member eating some bread while my neighbor went hungry. Taking that token was how I bridged the gap between my disgust with the narrative proposition and my imaginative connection to the game world we'd built.

They are in other words, along with the discussions themselves, tools not tactics. They add liminal negotiation space for you and your friends to dip in and out of as needed. A release valve for inevitable moments of confusion or deliberation. A moment of reflection always within reach.

I can't help but think about how affordances like these open up spaces for storytelling in a post-apocalypse that you just don't ordinarily see. These discussions, and the way the game provides allows you to register objections but refuses to let you to grind it all to a halt, are about as anti-individualistic a framework for storytelling as I can imagine. They are not good for telling the kinds of end-of-the-world stories that I've grown so tired of. Instead they emphasize the delicate resilience of a few people gathered around a table. They activate social dynamics like shame, pride, and shared memory over visceral questions of survival. Which means when you tell the story of The Quiet Year, you aren't all that interested in the apocalypse themselves, or the question of whether the community you make together will endure. Instead, the story you tell together about the end of the world feels like it's about shoring your own community up for what's to come. The Quiet Year uses the dire setting of the post-apocalypse to press on you and your friends' own resilience to hearing each other's disagreements, tolerating each other's grievances. It asks you to stay imaginative together even when you find each other's choices confusing, even offensive.

The Quiet Year is, it turns out, a sandbox for testing out your own fitness - not for your own survival, but for how you contribute to your community's health and well-being. It's a workout routine for the muscles you need to stick it out with the people you have in the places you live.

It's a machine for realizing how beautiful and thoughtful your friends really are.

That's all for this week. Let me know if this kind of deeper dive essay worked for you. And thanks for the patience as I got this week's edition out a bit late. Hope to see you next week at our regularly scheduled time.

Jordan Cassidy

Member discussion